<b>Birdsey</b>, R., N. P. <b>Gurwick</b>, K. R. <b>Gurney</b>, G. <b>Shrestha</b>, M. A. Mayes, R. G. Najjar, S. C. Reed, and P. RomeroLankao, 2018: Appendix D. Carbon measurement approaches and accounting frameworks. In Second State of the Carbon Cycle Report (SOCCR2): A Sustained Assessment Report [Cavallaro, N., G. Shrestha, R. Birdsey, M. A. Mayes, R. G. Najjar, S. C. Reed, P. Romero-Lankao, and Z. Zhu (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA, pp. 834-838, doi: https:// doi.org/10.7930/SOCCR2.2018.AppD.

Carbon Measurement Approaches and Accounting Frameworks

Two approaches to quantify carbon cycle components inform research and analysis for scientific studies as well as for management and decisions:

production-based or in-boundary accounting and

consumption-based accounting.

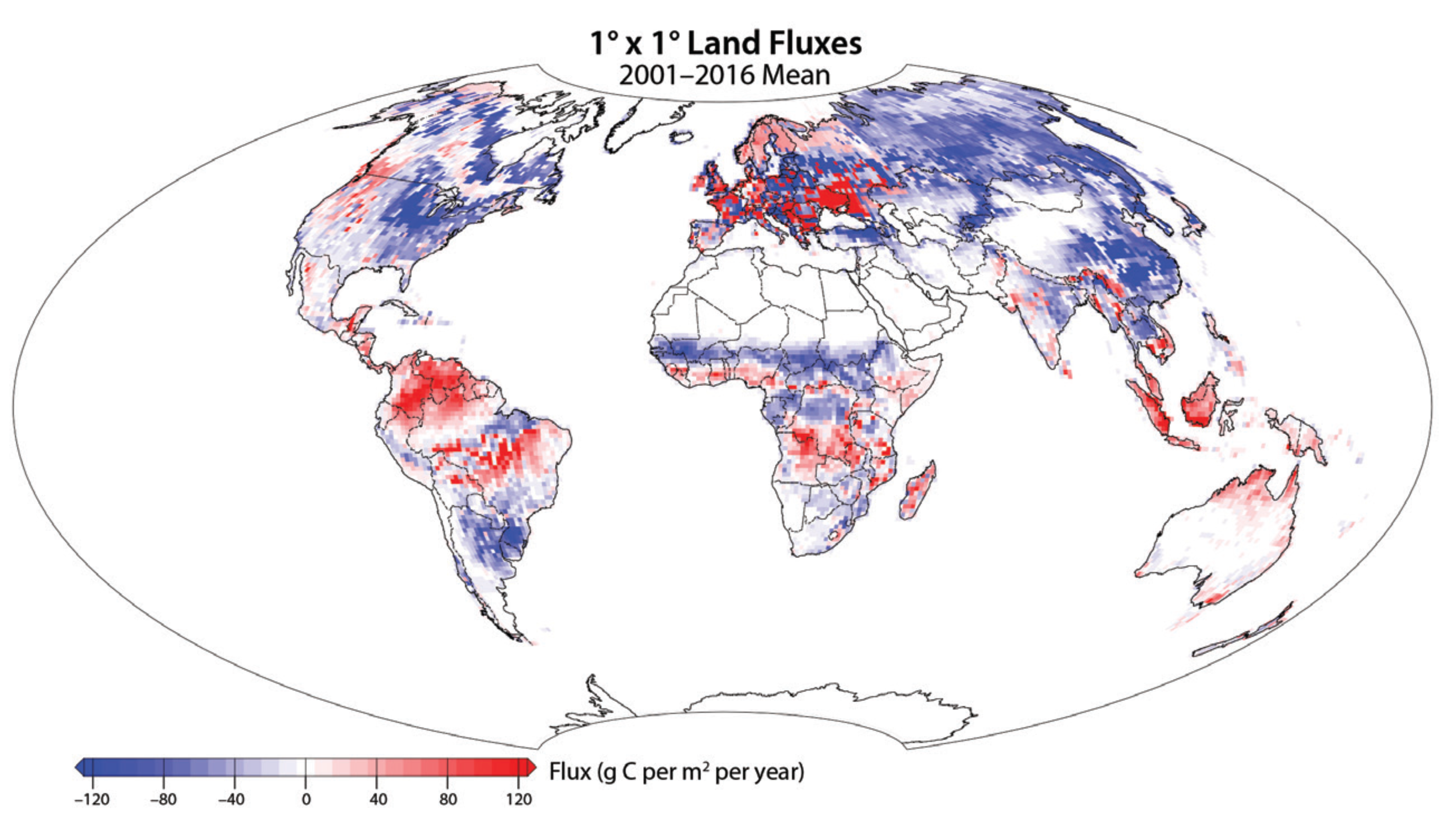

Production-based, or in-boundary accounting, considers CO2 and CH4 flows into and out of specific areas of land or water. For a hectare of land, net emissions result from, for example, photosynthesis, CO2 absorption by concrete, fossil fuel combustion at a power plant, and the decay of plants and animals on that parcel (see Figure D.1, this page). In practice, analyses of terrestrial ecosystems such as forests and grasslands also typically include lateral transfers of carbon among parcels (e.g., via erosion or streamflow).

Figure D.1: Carbon Emissions as Estimated Using a Production-Based Approach

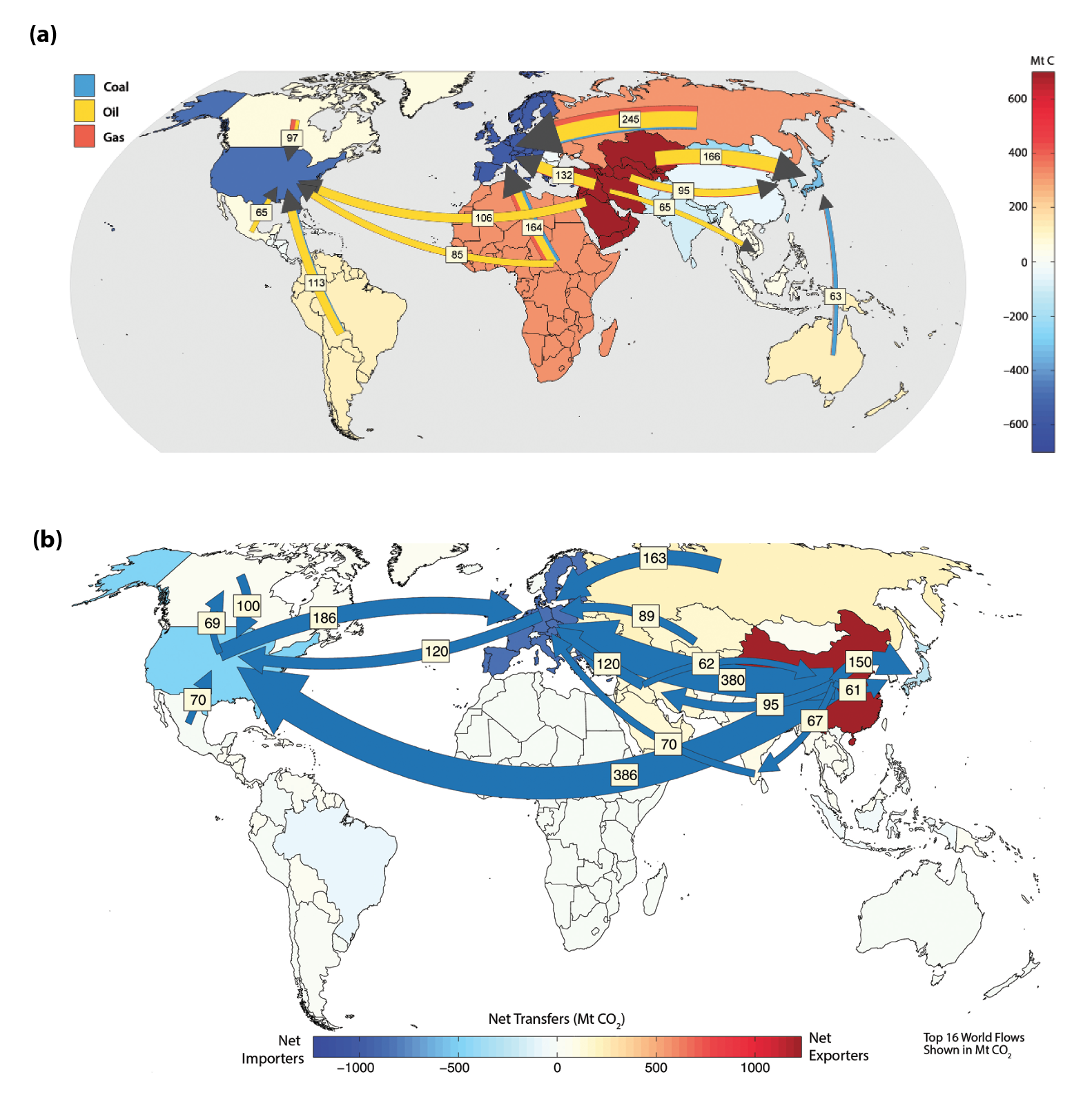

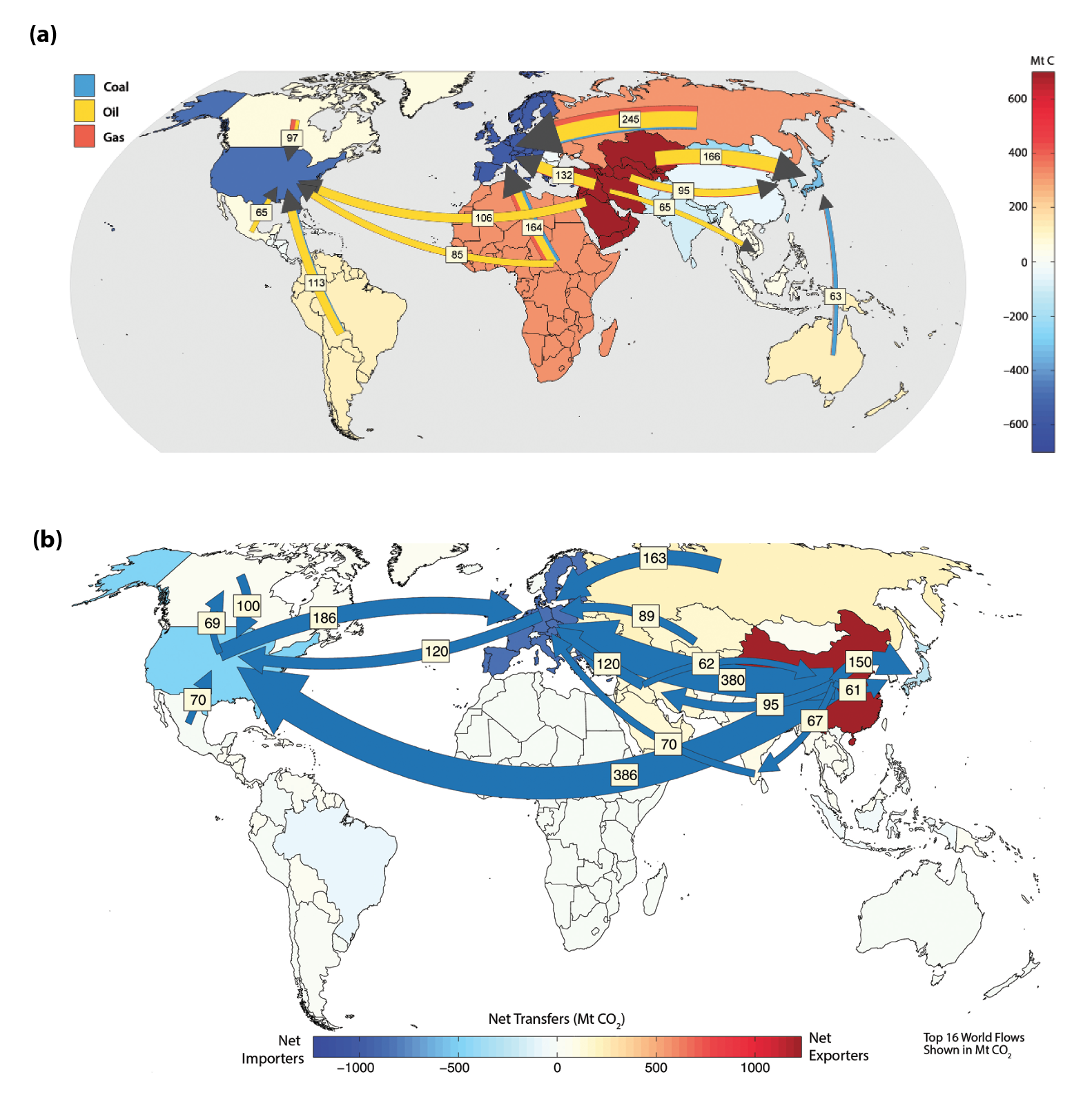

Consumption-based accounting assigns carbon flows associated with products and services (e.g., timber, electricity, food, chairs, televisions, and heat) to the places where people ultimately use those products (see Figure D.2, p. 837). This approach captures demand and trade as drivers of carbon emissions. For example, emissions from fossil fuel combustion during the production of electricity are assigned not to a power plant, but rather to the places where people use that electricity. In other examples, emissions from crop production are assigned to the place where the crop is consumed (by humans or animals), and carbon captured in trees harvested for timber is assigned to the timber mill or to the place where the timber is used. Quantification of these indirect fluxes typically employs a life cycle assessment framework that also can quantify the carbon stock residing in infrastructure and materials. Consumption-based approaches are more suited to revealing opportunities for replacing highly inefficient processes on the demand side with carbon-conserving processes (e.g., reducing GHG emissions by reducing food loss and waste), and to pointing out sectors in which demand for high-carbon products is strong (e.g., buildings that use excessive electricity compared to similarly sized buildings).

Figure D.2: Carbon Emissions as Estimated Using a Consumption-Based Approach

The difference between these two carbon accounting approaches is central to understanding stakeholder interests and deciding which accounting approaches to apply in different circumstances. How does responsibility for emissions divide, for example, between the person who finances a power plant that relies on fossil fuels and the people who own computers manufactured using electricity from that plant? How does responsibility for CH4 production by cattle divide among the people who own goods made of leather, people who transport cattle to the slaughterhouse, people who own feedlots, organizations that sell hamburgers, and people who consume beef? Questions like these, often unstated, determine which carbon accounting framework is most useful for informing debate, management, and decisions.

In some sectors, and at regional or national scales, production-based and consumption-based carbon accounting yield dramatically different results. In urban ecosystems, for example, where energy and goods are imported from sometimes distant suppliers into the urban domain, consumption-based estimates can yield a very different emissions responsibility than production-based estimates. Trade among nations also leads to dramatic differences in carbon flux estimates between production- and consumption-based approaches, with carbon-intensive production dominating some economies and consumption of those goods occurring primarily on other continents. At the scale of the whole planet, the two approaches necessarily converge.

Production- and consumption-based approaches reflect supply and demand perspectives, respectively, both of which inform management and policy decisions. For example, production-based approaches illuminate the consequences of different land-use patterns and the geographic areas where inefficient production systems offer compelling opportunities for improved carbon management. They also provide information about the relative importance of different processes to trends in carbon stocks; for example, they illustrate the magnitude of CO2 production from fossil fuel combustion in relation to CH4 production from ruminants and carbon capture by forests. Estimates from this accounting approach also correspond to direct measurements of CO2 and CH4 flows into and out of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems (e.g., with flux towers).

Figure D.2: Carbon Emissions as Estimated Using a Consumption-Based Approach

See Full Chapter & References