<b>McCarthy</b>, M. I., B. Ramsey, J. Phillips, and M. H. Redsteer, 2018: Chapter 7: Tribal lands. In Second State of the Carbon Cycle Report (SOCCR2): A Sustained Assessment Report [Cavallaro, N., G. Shrestha, R. Birdsey, M. A. Mayes, R. G. Najjar, S. C. Reed, P. Romero-Lankao, and Z. Zhu (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA, pp. 303-335, https://doi.org/10.7930/SOCCR2.2018.Ch7.

Tribal Lands

“Indigenous peoples in North America have a long history of understanding their societies as having an intimate relationship with their physical environments. Their cultures, traditions, and identities are based on the ecosystems and sacred places that shape their world. Their respect for their ancestors and ‘Mother Earth’ speaks of unique value and knowledge systems different than the value and knowledge systems of the dominant United States settler society. … Some Indigenous people believe that human and nonhuman individuals come from the earth and the ability to reach harmony among individuals is dependent on being a steward of the natural environment by giving back more than what is taken”

(Chief et al., 2016).

This chapter discusses how diverse Indigenous peoples in the United States, Canada, and Mexico affect and are affected by carbon cycle processes, and it explores the unique challenges and opportunities these communities have in sustaining traditional practices that are inherently tied to carbon stocks and fluxes on a range of landscapes. Carbon fluxes on tribal lands likely differ from those on analogous non-tribal land types (e.g., non-tribal forested, coastal, aquacultural, grassland, and agricultural lands) due to generations of Indigenous people following traditional agricultural and land-use practices. These practices, referred to as “traditional knowledge,” are rooted in an Indigenous worldview that holds humans responsible for the stewardship of all elements of the living and nonliving world around them. This chapter compares traditional agricultural, land-use, and natural resource stewardship practices with those introduced to North America by European settlers to estimate carbon fluxes on tribal lands relative to similar non-tribal land types.

Intrinsic differences in traditional and historical land-use practices on and off tribal lands can inform understanding of the carbon cycle and are the basis for considering tribal lands as a focused topic in this report. The lack of direct measurements of carbon stocks and fluxes on tribal lands requires that carbon cycle impacts associated with traditional practices be considered in comparison with non-tribal practices on similar land types, as data do not yet exist for creating tribal land carbon budgets. Formidable challenges resulting from the inclusion in this report of geographically and culturally diverse Indigenous peoples across North America are acknowledged. However, outlining opportunities for further exploration of traditional practices and how they could influence the carbon cycle is essential. Both the challenges and opportunities set the stage for identifying research needs that may empower Indigenous communities to expand their influence on decision making, affecting carbon management both on and off of tribal lands. Case studies are used to illustrate how traditional forestry, livestock, and crop production practices can impact carbon stocks and fluxes. Contributions to the carbon cycle from past and ongoing fossil fuel and uranium energy extraction and the role of renewable energy production on tribal lands also are covered.

7.1.1 Indigenous and Eurocentric Worldviews

The worldview of native communities (collectively referred to in this chapter as “Indigenous peoples”) from the United States, Canada, and Mexico is ecosystem- and watershed-based, inextricably bound to the land, and thus intimately connected to ecological systems integral to the carbon cycle. Management of carbon stocks and fluxes is encompassed within, and not easily separated from, the overall Indigenous perspectives that holistically link human and ecological health. These perspectives fundamentally differ from the Eurocentric worldview introduced to North American landscapes with the influx and migration of European settlers across the continent. A meaningful (albeit simplified) contrast between Indigenous and Eurocentric worldviews underpins the different approaches tribal and non-tribal communities have toward living on the land, which, in turn, influences how they manage carbon stocks differently on similar land types. Indigenous worldviews are rooted in a communal, spiritual, and cultural sense of place built on a web of connections between humans (living and ancestral) and nature (animals, plants, and minerals). Traditional agrarian practices are based on significant horticultural advancements using grouped planting strategies. One example is the “Three Sisters” agricultural system of mound structures in the eastern United States, where the climate is wetter. Another example involves planting seeds deeply in sand in the arid, rainfed agriculture of the western United States. These practices are native to ancestral landscapes and ecosystems and have integral ties to ceremonial practices and seasonal cycles. In contrast, Eurocentric worldviews are more uniformly applied and were built on the notion of altering the natural world. Agricultural practices introduced to North America by European settlers rely heavily on plowing or tilling fields, which required making significant changes to the land by clearing vegetation, including clearcutting forests, to accommodate planting.

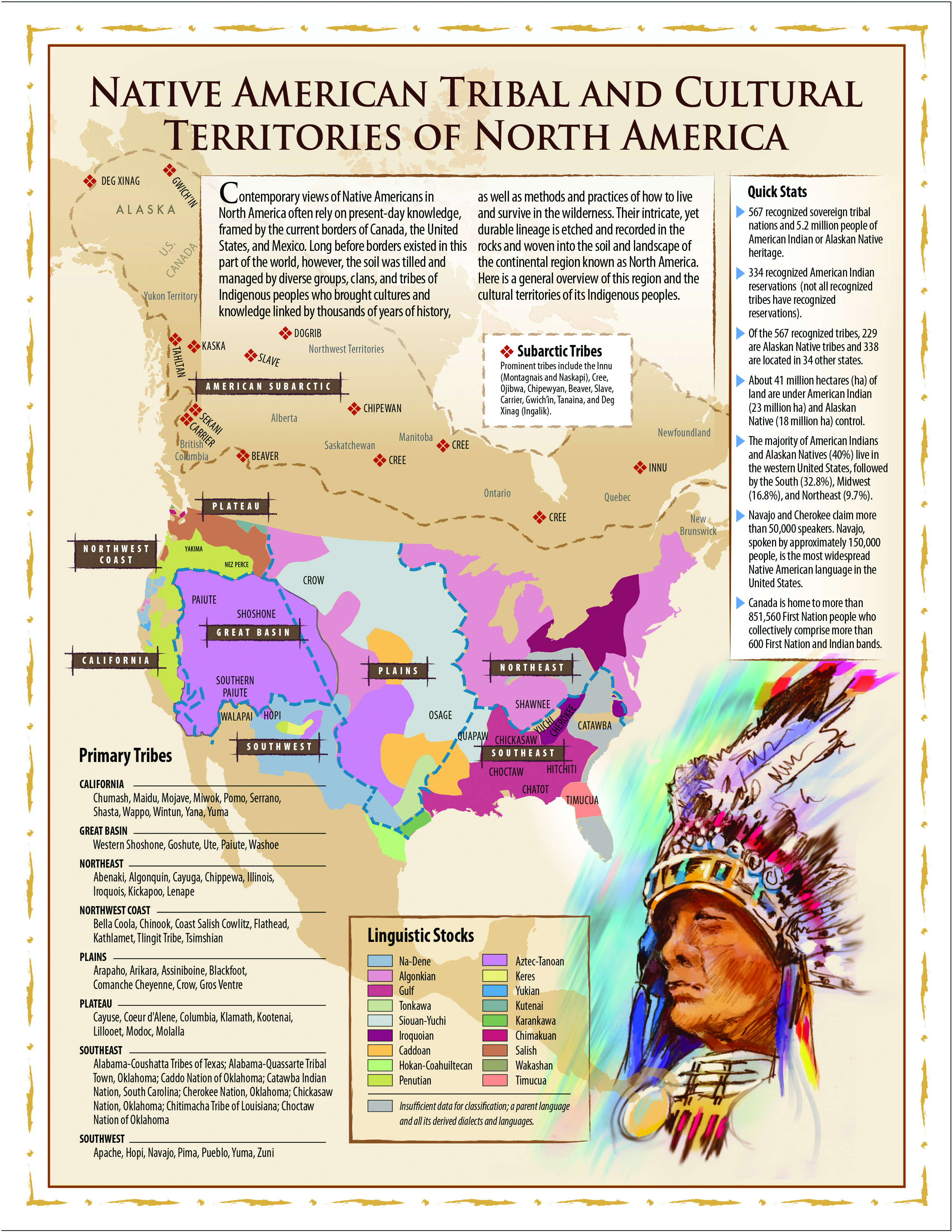

Traditional practices tied to a holistic approach to living in balance with the drivers of air, land, and watershed change are fundamental for Native American tribes in the United States, First Nations Aboriginal peoples in Canada, and Ejido communities in Mexico (Chief et al., 2016; NCAI 2015; Blackburn and Anderson 1993). These communities have ancestral ties to the land that span thousands of years. Many Indigenous communities are agrarian based, with their livelihoods and cultural identity intimately associated with the health and well-being of the plants, fish, animals, and natural resources of their ancestral homelands (see Figure 7.1). Livestock grazing and crop production; seed, nut, and plant gathering; and fishing and wildlife hunting are essential for cultural ceremonies, community wellness, and economic prosperity (AANDC 2013; Assies 2007; Chief et al., 2016; Tiller 1995, 2015).

Figure 7.1: Native American Tribal and Cultural Territories of North America

7.1.2 Carbon Cycling Considerations Unique to Tribal Lands

Carbon cycling among reservoirs in the atmosphere, terrestrial vegetation, soils, freshwater lakes and rivers, ocean areas, and geological sediments is integral to native landscapes. That said, discussions about how Indigenous peoples are affected by carbon cycle processes are different from similar discussions related to non-tribal lands, thus warranting separate consideration due to several key factors:

Scientific data and peer-reviewed publications pertaining to carbon stocks and fluxes on reservation lands are virtually nonexistent, which makes establishing accurate baselines for carbon cycle processes problematic.

Traditional knowledge about practices with bearing on carbon stocks on native lands (e.g., intergenerational stories, practices, and observations) often does not conform to mainstream science prescriptions for data gathered and analyzed for technical reports, including this report.

Indigenous communities throughout North America are culturally distinct, with their own languages, practices, spiritual and cultural systems, governance structure, and deep connections to their lands, hence generalizations across North America may be of limited value.

Native American communities in the United States and First Nations of Canada (but not Ejidos in Mexico) are recognized as sovereign nations with their own distinct policies, laws, and practices that may impact carbon stocks and fluxes on native lands.

Native communities are heavily affected by the policies and laws of surrounding national, state, provincial, and local governments, as well as the economic and social drivers of non-tribal landowners and energy and natural resource extraction industries. Land-use decisions by native communities are influenced by high levels of poverty, unemployment, and health challenges.

Complex Native American land tenure and water rights laws enacted by the U.S. and Canadian governments during the last two centuries have fractionated tribal land ownership, producing checkerboards of land types on reservations. In the United States, some of these lands are held “in trust” by the federal government, while others have been allotted or sold as “fee simple” lands that may be owned by one or many tribal or non-tribal individuals and subject to both tribal and non-tribal laws (Colby et al., 2005; McCool 2002; NCAI 2015; Pevar 2012; Thorson et al., 2006).

Opportunities for managing carbon stocks and fluxes present unique challenges to Indigenous peoples because of external stressors that constrain or complicate a community’s ability to sustain traditional practices that affect carbon processes. These include:

The historical practice by the U.S. and Canadian governments of relocating Indigenous peoples from their expansive ancestral homelands to reservations on “marginal lands” in remote areas, which may or may not be contiguous with their sacred places. Similar disenfranchisement of Ejido communities has occurred in Mexico, where these isolated communities have little or no self-governance (OHCHR 2011; Pevar 2012; Russ 2013).

Close cultural and economic ties to natural resources, geographic remoteness, and economic challenges make Indigenous peoples among the most vulnerable populations to climate change. These include (but are not limited to) tribes being displaced by rising sea levels and thawing tundra and those subjected to increased heatwaves, droughts, and extreme weather events that disrupt the traditional seasonal cycle and affect native fish, plant, animal, and water resources (Bennet et al., 2014; Melillo et al., 2014; Redsteer et al., 2018; Krakoff and Lavallee 2013).

Colonial practices of relocation, termination, assimilation, and coercive exploitation of native lands have divided Indigenous communities and limited their ability to influence surrounding national and regional government decision making related to land use and carbon cycling (Anderson and Parker 2008; Bronin 2012).

European settlement mandated that native communities convert traditional agriculture practices to Eurocentric crop and livestock production, which forced changes in landscapes, water supplies, and community health (Reo and Parker 2013; Kimmerer 2003; Thorson et al., 2006).

Daunting socioeconomic challenges, including high levels of poverty and disease, demand significant time, attention, and resources and can influence land-use decision making by individuals and tribal governments. Native communities are heavily reliant on a wage economy and are subject to different federal policies than other citizens in their respective countries. The poverty rate for Native Americans living on reservations in the United States is 39% (the highest in the country), the joblessness rate is 49%, and the unemployment rate is 19%. Native health, education, and income statistics are likewise lower than those for any other racial group in the United States (NCAI 2015, 2016; GAO 2015; Indigenous Environmental Network 2016; Mills 2016; Regan 2016; Royster 2012; Notzke 1994; Assies 2007; Frantz 1999).

See Full Chapter & References